if a man directed ‘the ascent’ it would be considered one of the greatest anti-war films

why don’t we give larisa shepitko her flowers?

Ask anyone who is relatively familiar with film what the best anti-war (or, for the sake of argument, war) movie is, and you’ll probably hear one of the following: Apocalypse Now, 1917, The Deer Hunter, Paths of Glory, Dunkirk, Schindler’s List and, of course, Come and See.

Apart from how obviously American/Eurocentric most of those movies are—I feel there’s better candidates to speak on that issue than myself—it’s also worth mentioning that not a single one is directed by a woman. That’s not to say that I don’t think the titles I’ve seen from that list are well-made or undeserving of praise, but it opens up a discussion that sometimes feels beaten into the ground: where the fuck are the women?

I’m not here to lecture anyone on what we already know; women have always been a very prevalent part of war. They’ve been nurses. They’ve provided intel. And even in cultures where women have not been allowed to actually be soldiers, they’ve been the forces behind what kept soldiers fed and clothed. They’ve kept things running “back home”. But anyone who knows anything about history knows this.

I say this as someone who thinks wars and militaries’ “goods” have never outweighed their evils: why are war films only ‘revolutionary’ when they’re made by and for men?

That leads me to my prime example, Larisa Shepitko’s 1977 feature The Ascent.

The film centers around Sotnikov and Rybak, Soviet partisans who are sent to get food and supplies from a nearby farm for their comrades. Sotnikov was a math teacher before the war. While at the start of the movie, it seems he’s the weaker of the pair, he proves to actually be the stronger-willed and most morally consistent. A lot of the narrative is made up of Soviet men trying to avoid German soldiers.

I went into my first watch without any prior knowledge—it didn’t take long for me to figure out that The Ascent wasn’t directed by a man, though.

Beyond the fact that the movie has some of the best composition and use of lighting I’ve ever seen, it was also empathetic. Blatantly. In war movies directed by men, there might be kindness; but especially in the 1970s, kindness had to exist under the guise of “comradery”. Kindness is too feminine, and therefore too weak, in the setting of a war story.

In The Ascent, kindness just is. It’s used sparingly, but it doesn’t pretend to be something it’s not. And as strong of an opinion as it might be, I truly believe men have a more limited understanding of empathy than women. Even in Francis Ford Coppola or Stanley Kubrick’s most empathetic moments—if Kubrick even had those—I think it’s something that required a serious amount of effort.

Shepitko was able to seamlessly balance the moments of affection in The Ascent with the bleakness, and perhaps the rage, of the rest of the movie. For all of the talk of women not being able to write or direct serious movies without “bleeding hearts”, I’ve yet to see a man make a movie as effective as Shepitko’s final feature.

For anyone who’d like to contest that point, I implore them to watch the “moon scene” from The Ascent—for context, Sotnikov has been shot in the leg by German forces while trying to evade them. He can’t possibly get away with a bad leg in deep snow. Sotnikov declares that the enemy “won’t take him now”, then gets into position to take his life with his own firearm. There’s a long moment where we hear gunfire grow closer, and the camera settles onto Sotnikov’s face—in casting Boris Plotnikov, for whom this was a debut role, Shepitko sought out an actor who’s expressions mirrored images of Christ—and we see that he’s looking up at the sky. When the camera cuts to the next shot, it’s of the moon. It could be debated that Sotnikov is coming to terms with his own demise or that he realizes he doesn’t want to die; to me, either is plausible, but I prefer to think of it as the first. Sotnikov, former schoolteacher, is taking this last moment to make peace with the fact that he’s seemingly dying alone and for nothing at all.

Sotnikov is rescued by Rybak a few seconds later. But it’s that sequence, probably less than two minutes long, that cemented The Ascent as the most meaningful anti-war film I’ve ever seen. When we speak about despair, we often cite Dostoyevsky or Kafka: ultimately, it’s a brief segment from a movie directed by a woman that I think of first when talking about the subject.

Up until last November, I thought Come and See was the most damning portrayal of war and what it does to human beings. And while it’s one of the only movies I physically cannot bring myself to rewatch—it’s excellent, but it literally makes me feel ill—I can now recognize the influences that Larisa Shepitko had on it.

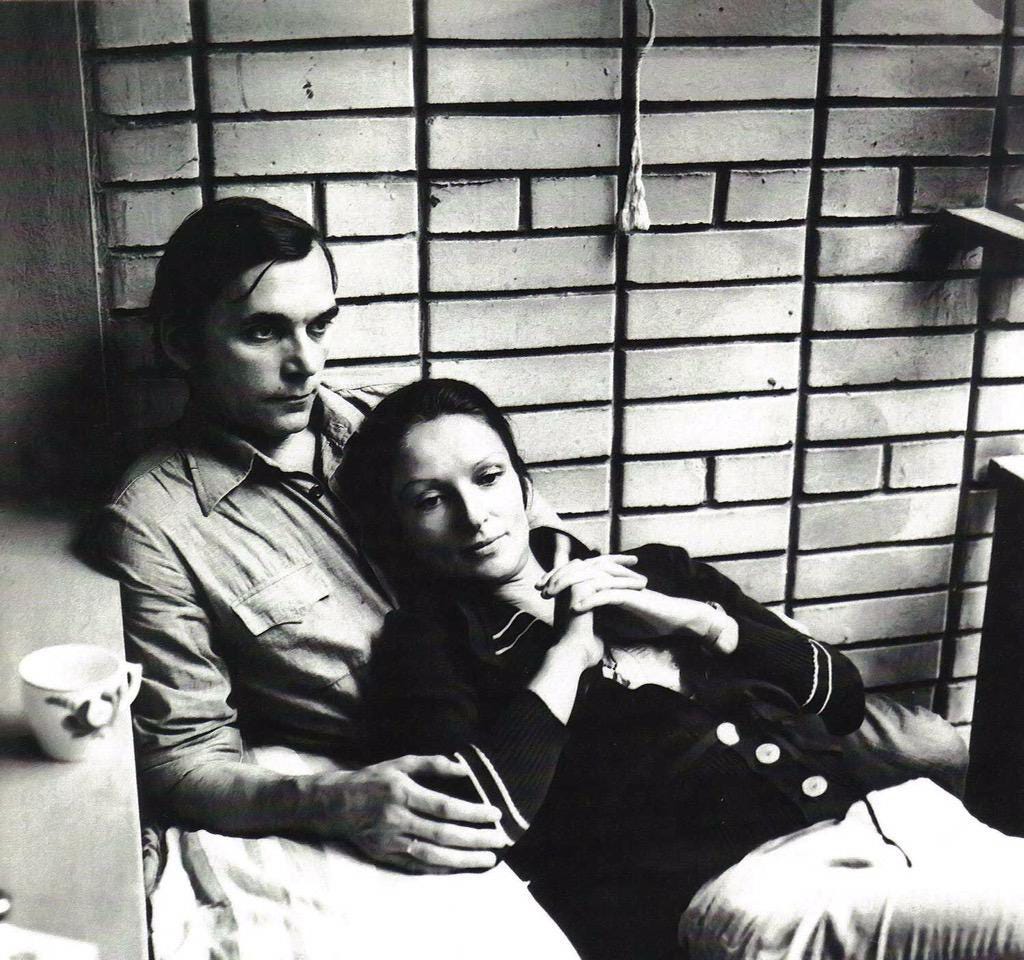

Elem Klimov, who directed Come and See, was married to Shepitko. His wife was tragically killed in a car accident while location scouting for her next film, cutting an already incredible career short. And while the two war movies aren’t entirely comparable, seeing as one is through the perspective of the child and the other through a full-grown man, I think it’s undeniable that Shepitko’s work, specifically The Ascent, had a massive impact on her husband’s own filmography. There are certain shots in Come and See, especially those of the character’s faces, that remind me overwhelmingly of Shepitko.

The thing that is most upsetting to me about the lack of discussion surrounding The Ascent and Shepitko in general is that she was not an unknown by any means.

Less than six women have won the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival, the highest award available at the event: the second to do that was Shepitko in 1977. But despite best efforts by film preservationists and enthusiasts alike, it seems that Shepitko’s work remains criminally underrated. I’d heard of Klimov years ago, even before I’d expanded further into non-English cinema, but never once the woman who was arguably his biggest inspiration.

If Shepitko was a man, would this be the case?

I guess I can’t definitively say. I can only hope that anyone who appreciates movies, especially people looking to be directors and screenwriters in the future, will come to appreciate Larisa Shepitko—who braved injury and illness in order to create her work—too.